Smurfing – A design problem, not a toxicity problem

Overview

Smurfing, the act of creating, or utilizing low ranked accounts to play below your skill level in online games is becoming more and more of a prevalent problem for players and designers everywhere. The majority of players who queue up on any given night, expect a reasonably balanced match with opponents who they have a fair, 50-50ish chance of beating. However, with the majority of competitive online titles going free to play, there is an incredibly low barrier to manipulating your rank for any player seeking to alter their experience manually. It’s often just accepted as a reality of free to play titles, and the majority of solutions presented by developers have been related to stamping it out via detection, bans, and forced identification of account owners (2FA, IP Bans, etc.). However, I believe the smurfing problem is one that speaks to a failure of design, and is a message being sent by players that they’re not happy with established matchmaking systems, and the games surrounding them. In this post, I’ll go into detail on why I believe smurfing isn’t just power-tripping, and speak to some creative ways I believe that game designers going forward can help avoid creating the incentives that cause this behaviour.

Understanding The Problem Space

Most modern games use some variation of Microsoft’s “Trueskill 2” system, which derives their own original Trueskill system, which derives from the Elo rating system used in Chess, which derived from the Harkness rating system, which was probably derived from something else somewhere at some point. Despite the rich history, these systems are ultimately pretty simple, and more or less equate to:

“Everyone starts with some points, and then they win points for winning, and lose points for losing. Get a big enough sample size, and points represent who good and who bad.”

Microsoft’s research division probably

I’m over-simplifying, there are of course some modifiers and deeper math if you want to review the papers and algorithms yourself, but ultimately, most games just make some tweaks to the above, and fire away. Why not? It works. The majority of the player base ends up as close to 50% as possible with minor deviations, and everyone can rest easy knowing that the play button will pair them with someone just as bad as they are.

This naturally creates the assumption that by the action of subverting the system as is, the players who smurf are simply dissatisfied with their “fair” 50% wins. They want to win all of their games because winning games feels good. They’re trying to cheat the system that’s supposed to distribute wins evenly to give themselves more than everyone else. While there may be a grain or two of truth in that, I think this line of thinking supposes an inherently infallibility of the system itself and ignores some points of legitimate criticism of this typical matchmaking experience. What if we took a step back and asked ourselves what other incentives this system could possibly be creating that drive this behaviour? What other emotions and thought processes might a player go through to arrive at the conclusion that they’d rather play “down” from where they’re supposed to.

“One thing that we have learned is that piracy is not a pricing issue. It’s a service issue. The easiest way to stop piracy is not by putting antipiracy technology to work. It’s by giving those people a service that’s better than what they’re receiving from the pirates.”

Gabe Newell – Speaking on the issue of software piracy

In a lot of ways, I think this problem is analogous to the piracy problem Gabe Newell references in this quote above. He was speaking to the fact that Steam found success in markets that they were warned against entering due to rampant piracy. Some of these markets became Steam’s biggest successes, because the problem wasn’t necessarily just that people there were thieves. It was that the friction to acquiring games was lower through piracy than it was through legitimate means, if there were any in the first place. In many ways, I believe smurfs are seeking an experience that is under served by game developers, and their subversion of established systems is a symptom of that, not simply a toxic and undesirable human evil that emerges due to online anonymity such as other behaviours like online harassment, trolling, griefing, etc.

Below, we’ll start to dissect some of the individual problems I believe to exist with traditional matchmaking, how they relate to smurfing, and talk about actionable solutions to each of these design problems.

Ladder Anxiety and Reward Structures

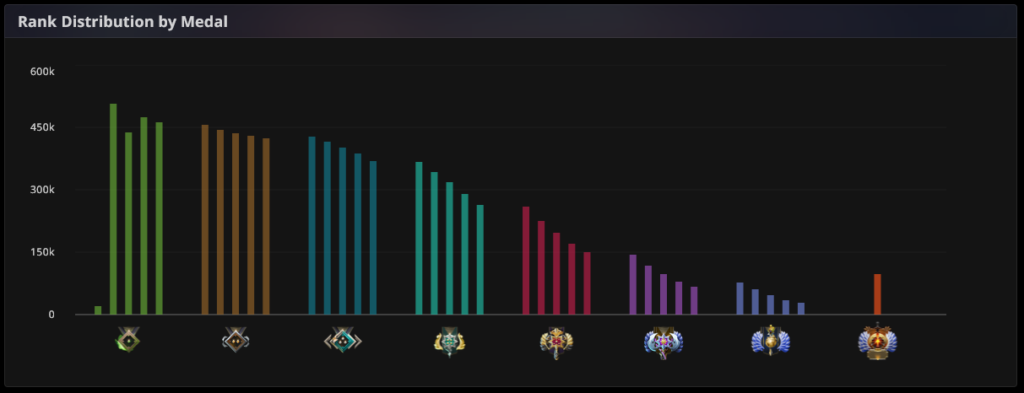

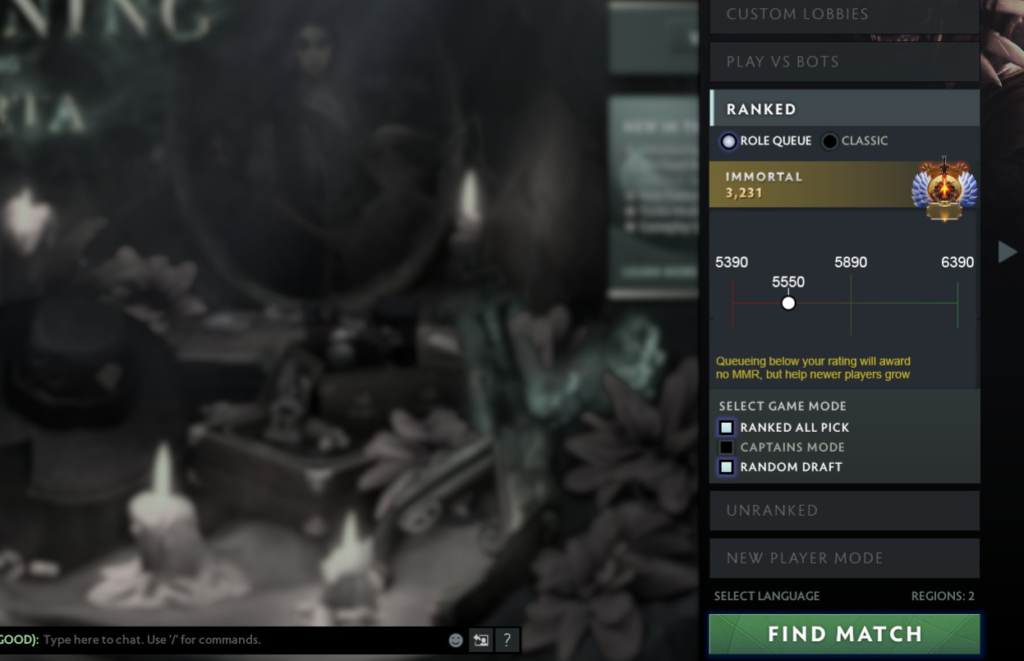

The first major area I want to delve into, is the reward structures of the games themselves. Most competitive games treat their rating points (Elo, MMR, etc.) as the “carrot” for players to pursue, intentionally or not. Whether the actual points are displayed such as in games like Dota 2, or obfuscated like in “tier-based” systems like Rocket League, Valorant, etc. the persistently visible ranks tell players that they should try to get to, and maintain the highest score possible. While this makes sense on the surface, a player’s journey upwards in any given game is rarely linear, and as they explore new strategies, practice unfamiliar characters, or simply hit rough patches where they play worse for any given reason, they’re put at odds with the reward systems in place. Their “progress” is stripped away, and for many this can be an incredible source of ladder anxiety. The feeling that deviating from their current optimal strategy will put them behind. This is highly visible in rank distribution graphs such as the one of Dota ranks below. Each medal has a visually notable plateau, or bump at the lowest rank, likely consisting of players who eek their way out of the previous medal, and therefore achieve a new “title”, and cease playing. If all players played continuously, we would expect this distribution to be perfectly smooth between medal tiers.

This issue is not entirely a fault of the rating systems. They’re doing their job of creating balanced and fair matches, but by making it visible, and tracking it across small samples, even down to individual games, we are invoking a powerful sense of reward and punishment that gets in players heads. Since player’s titles are tied directly to their current rating score, we lead players to behaviours that optimize that rating in the short term. At worst, boosting or cheating, and at best, just narrowing their play so much that they begin starving themselves of variety.

For players, they want to be proud of their peak, or their potential. They want allies, opponents, and friends to know that they “are”, or “can be” players of X rating when they’re on their game. By drawing a direct line between a player’s current rating, and their current social status in the game, especially in highly competitive environments, we lead players to be far more sensitive to the short term fluctuations that are natural of a system that’s always calibrating and dependent on multiple factors.

This relates to smurfing, in that this negative reinforcement to short term variations causes players to feel like they’re damaging their reputation or standing when they want to explore the game. If they decide to try a new role, or a new character, or to learn a new playstyle, they know that they’ll hit a short term downturn, and in turn, potentially lose the “achievement” that they worked hard on, despite likely being able to go back to the way they played the game before to regain it. This creates incentive both for players to only play a narrow band of “styles” that they excel at in ranked play, and to find alternate places to play that don’t affect their rating when they want to explore, such as unranked games, or more commonly, smurf accounts.

This may be more or less severe depending on the variability of roles, characters, and strategies to play in a particular game. This is likely far more true for a Dota player where each player role is distinct, and the hero roster is beyond 120, than in Valorant or Counter Strike where roles are soft delineations and physical acumen is a more defining factor.

So how can we resolve this? Well I think the major key to this point is that we should allow players to hang on to and share their peak just as much or more than their current rating. Maybe it’s a seasonal thing that resets every few months, or maybe it’s permanent with some clear labelling of current versus all-time, but a player should be able to show off and be proud of the top end of what they achieved. This is key because it allows players to slump without losing perceived progress on the ladder.

As well as emphasizing peaks, we should also explore more granular rating systems. Maybe a player has a rating, or a modifier that only tracks for each game with a particular role or character, and a “core” rating which tracks all games played. Then their rating for a given match is the half-way point between the core rating and their role rating. It’s up to the developer to figure out what’s right for their particular game, but by getting more granular about the individual scenarios a player can find themselves in, the less likely we are to induce anxiety when a player is outside their comfort zone, and the more honest they can be with the game about how they’re going to fare in a given match. A truly obsessive designer focused on this problem could even explore rating modifications for days of the week, times of the day, actions per minute, historical performance with allies or against enemies, etc. By better understanding the different states a player may be in, the better we can accommodate them, and make them feel less like they need to curate their own experience in a system-breaking way; smurfing.

The Benefits Of Uneven Games

The next thing I want to tackle, is the supposed infallibility of typical rating systems themselves. One of the key assumptions made by designers when creating their matchmaking systems, is that a perfectly even, 50-50 match, is the optimal outcome of a rating system. Obviously it’s the most fair, but should it be applied as a blanket solution to all players?

When I first started gaming competitively, I played in a time before MMR. I played in a time of lobbies and servers. When I booted up a game of Command and Conquer, or Counter Strike, or Starcraft, instead of a queue button, there was a list of “rooms” I could join, usually with some stupid name like “noobs only” or “10 mins no rush”, and I would just click one, tell the host to gogogogogogogogogogogo and hope he wasn’t AFK. The person hosting that lobby could be anyone. A world champion who had played the game for every minute of his waking existence, or someone as bad as me who had picked up the game 2 days previous and barely finished the campaign. Because of this, I got my ass handed to me. A lot. I recall when I first started playing C&C3, I had 46 losses before stumbling across my first win. The game allowed you to reset your profile though, so I just reset it over and over so that it didn’t look like I had a 2% winrate.

Was that in particular a fun experience? No. If I was older and had less free time, that might have made me quit. However, what it did do, was accelerate my competitive growth in the game incredibly fast. Instead of playing games where I could make mistakes and win anyways, I had every mistake I was making ripped out of me and slapped on the battlefield for all to see. I could watch a demo playback and see exactly how my opponents managed to get those units over to my base so damn quick, and relive the carnage that ensued. After that 47th game, I started to pick up wins. Slowly at first. One every 4-6 games. Then every 2-4 games, then every other game, and eventually I was winning more than I lost. I crawled over the bell curve peak of the player base average, and was rewarded with both a feeling of personal accomplishment, and an experience that accurately reflected the work I’d put into the game. I was better than maybe 60 or 70% of the player base, and thus won, 60-70% of my games.

“I have not failed. I’ve just found 10,000 ways that won’t work.”

Thomas Edison

The point of the above recollection isn’t to suggest that we should go back to lobbies, or a fully randomized matchmaker, but to illustrate that improvement is derived from hardening oneself against tougher opponents. There is value in having players experience an ass-kicking every once in a while, and a truly dedicated player, may actually seek it out as a regular experience. When I was on my quest to become a Dota 2 pro, one of my major difficulties in improving was finding places to play that would truly undress my weaknesses. The typical pub experience had everyone around me making the same mistakes as me, and failing to punish the mistakes I was making, leading me to a bit of a stagnant plateau, where the things that I did didn’t work against better players, and the things that better players did against me were alien because no one at my current level did them. I pined for better competition, and looked for inhouses, scrims, and competitive opportunities in higher levels of play, but they were few and far between, and it was difficult to build habits around them, because between every high level game I did find, was 100 games at my current level.

So what if games allowed players to deliberately skew their ranks? What if there was an option to deliberately play up from your level, while others could deliberately play down? We’ve already covered why a player may be sensitive to playing at their own level and thus seek to play down via smurfing. Why not allow that, and pair those players with players seeking to improve, or step up? The system could have incentives tied to it, such as boosted rating gain for the lower level players, with protected or minor rating losses for the higher ranked players to abate players avoiding the mode due to risk aversion. It could include in-game features that help foster the knowledge transfer, such as a prompt after the game for the higher level players to provide feedback for the lower level players, or an in-game voice coaching system like Dota 2 has. Some version of this could allow for players to choose on any given day whether they feel up to playing at or above their level, or if they want to take it easy for an evening.

What are players really asking for?

Finally, I want to talk about the deficiencies of competitive games that create a desire to smurf. In my personal observations, there tends to be a common thread that connects smurf experiences in each game where it’s prevalent, and not all are the same.

For example, in Rocket League, it’s used to be very common to encounter smurfs who were practising aerials, air juggles, and flip resets in low ranked games. These are high-risk maneuvers which often put a player in a compromising position if missed or executed poorly, so players will often steer clear of using them in their own games until they’re confident that they’ve mastered the techniques. So what were these players communicating via their smurfing? Well, the training modes in base Rocket League were a great tool added by the developers, but they lacked the feel of true gameplay. There was no opponent attempting to make saves, and no pressure being applied to force you to adapt. Then Psyonix added workshop map support, which allowed for tons of creative training maps to be generated by the community. In many ways, these maps are better than playing against live opponents in honing these skills. While I still see the occasional smurf in Rocket League playing party games, or in tournaments to farm cosmetic rewards, the stylish air-dribblers in my 1v1s are much fewer and farther between nowadays.

In Dota 2, one of the most common reasons that I see smurf accounts used, is to play with lower ranked friends. This is the reason I have one of my own. When my girlfriend got into Dota 2, I wanted us to be able to play together, but the experience was frustrating, because the matchmaker would typically pair us with players at, or near my MMR, and as such, the players on the enemy team would feast on her, while I played a game that was maybe 5-10% weaker than a typical game for me. I had to spend a lot of energy in each of these games, trying to keep enemies from getting out of control on the gold they acquired from her, while she simply tried to avoid dying. It wasn’t fun. She was hardly playing Dota as a typical player would recognize it, feeling like a burden, and I was trying far harder than I typically do in my solo games, trying to remain in a dominant position in the game to eek out a win. On a smurf, we played closer to her rating, and were able to have a much better time. She was able to contribute to the game, and I was able to turn off my try-hard brain, allowing me to socialize with and coach her in a way I couldn’t when I was trying to hold players of my calibre at bay. Despite me playing down, our win rate in these games still holds fairly steady near 50%.

So what is there for Valve to learn from that? Well, their party matchmaking algorithms for players of disparate skill levels aren’t great. I think in an effort to avoid matching high variance parties with mid-rank parties where a good player could feed off of the mid-rank players, they altered the way matchmaking works to pair high-variance parties with parties closer to the rank of the top players in the stack. This results in the low ranked players in the high-variance stack having a terrible time, and thus creates an incentive for those groups to bring their perceived skill closer together.

As a second Dota example, smurfing became a very common practice in the earlier years of Dota 2 when professional players simply stopped being able to find games. Due to their high skill ratings, the system simply deemed players too far apart in skill to be placed together, and the best players in the world were left sitting in multiple hour-long queues to play a single game that might end in 20-30 minutes. So what did the players do? They made accounts that put them back in the main player pool and played games. None of them wanted to have to do that, but they simply couldn’t play the game otherwise. Valve’s matchmaking had failed to account for the far reaches of the bell curve distribution when it thins out too much.

Other systems account for this by doing periodic resets, where that bell curve is “bunched back up” by re-calibrating players at the top of a fixed range, and Valve even did this for a period, before ceasing to maintain it and allowing an MMR distribution that once capped out around 7,000, balloon to a point where top players today have 11-12,000.

To conclude here, I think every smurf problem is unique, but shouldn’t be viewed just as a problem of “power-tripping abusers”. Often the players engaging in these behaviours are lacking an experience that you may be able to offer them as a part of your game. Maybe your algorithms need some work. Maybe you need better training grounds or rating-free modes that players can improve themselves in. Maybe it’s something else entirely. Whatever it is, do some user research, and explore what your players may be craving that you don’t offer. While we can’t dole out higher win percentages for the sake of fairness, maybe we can help them improve, socialize, or play casually in better ways, and remove some of the incentives we’ve created to skirt our desired behaviours as designers.

Conclusions

To summarize, while smurfing creates negative consequences for the players encountering them, as designers we need to be more cognizant of the reasons why a smurf experience is preferable to a fair one. While some smurfs may simply be chasing the power trip of an 80% winrate, I’d wager that the majority engage in it because of some of the emotional and experiential triggers we discussed above. Instead of fighting this battle with a mindset of reports, smurf detection, ban waves, and 2FA restrictions, why not explore novel ways we can improve the game experience for players at their own level so they don’t feel the need to escape it.

To recap:

1. Be aware of how your game rewards progress, and how it may create “ladder anxiety”. Over-emphasizing a player’s rank or stats, and tying rewards to upward progress may cause players to be too precious about their rating, and manipulate the system to avoid short term losses.

2. Explore ways you can provide better training tools and low-pressure environments for players. Often, competitive games feel too heavy for players, and when they want to crack a beer, play with friends, or try new strategies, they see smurfing as a way to relieve that pressure while still enjoying the game they love.

3. Do some user research and figure out what in particular is driving people to use smurf accounts in your particular game. While some may just be doing it for fun, you may stumble into some deficiencies in your established pairing algorithms, features, game modes, or community building that can be addressed to pull users back to a satisfying experience on their main accounts.

Thank you for taking the time to read or listen to this article. If you’d like to share feedback or discuss further, feel free to reach out on social media. Always happy to have my brain picked.